Warning

The following may contains spoilers for The Mandalorian Seasons 1 & 2!

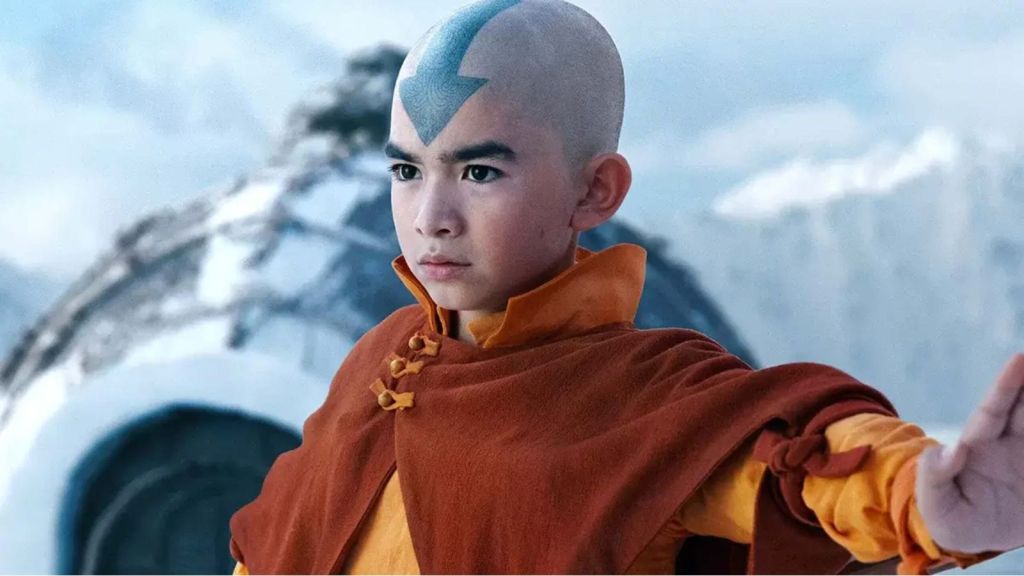

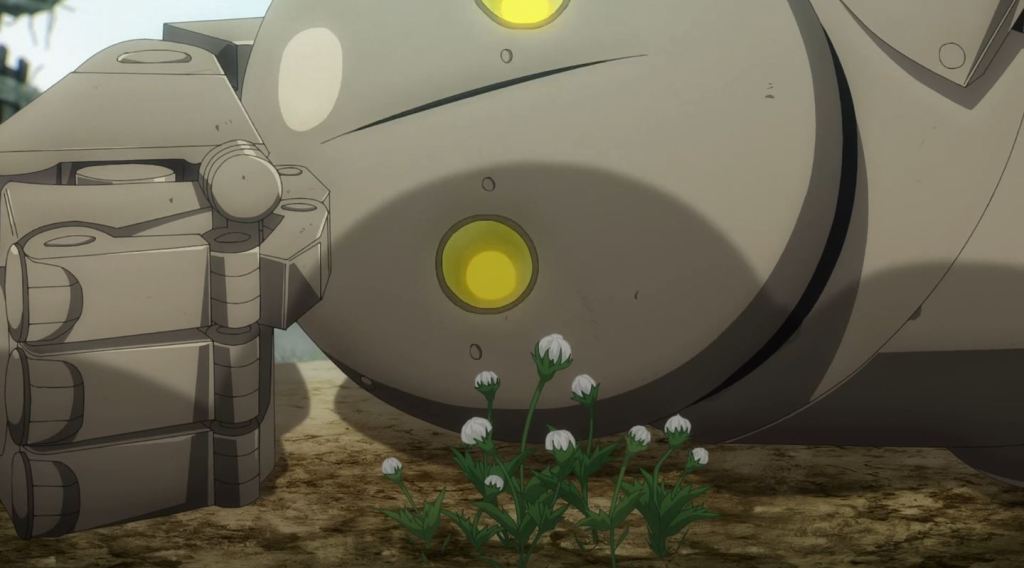

The Mandalorian is back in full stride on Disney+ and millions of viewers are already enthralled in Din’s mission to clear his ‘Apostate’ status. On the surface, The Mandalorian is Star Wars through and through, it’s got droids, blasters, spaceships, and the colossal selling point that is ‘Baby Yoda’, but at its core, The Mandalorian is a homage to one of the most influential genres in cinema history… the Western.

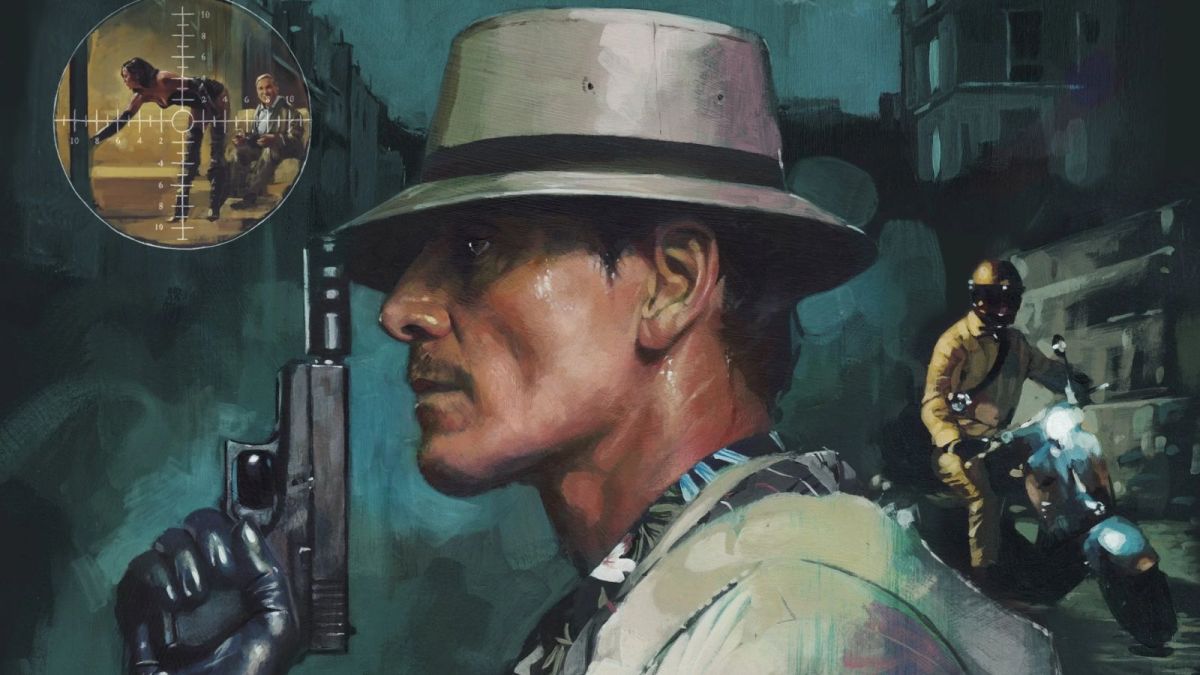

Since the show’s pilot in 2019, The Mandalorian has proudly displayed its Western influences in myriad ways. The show’s aesthetic and mise-en-scene often incorporate conventions of the western genre, from wide-lensed landscape shots of barren deserts to the iconic ‘cowboy shot’, a cinematic composition used in nearly every Western since The Great Train Robbery (1903). Din is often framed using this technique, displaying the character from the hip upwards to allow his holstered gun to be shown in the shot.

Almost everything about Din’s character design is based on the western genre. His armour and clothing, most notably his shoulder cape, are heavily influenced by Clint Eastwood’s ‘Man With No Name’ in Sergio Leone’s revered Dollars Trilogy (1964-66). Din’s initial profession, a bounty hunter, is a trope long associated with the western genre, featured in classics like True Grit (1969 & 2010) to more modern takes like Slow West (2015).

As well as mirroring dozens of influential Westerns, Din’s role as a bounty hunter reflects his characterisation as ‘morally grey’, a theme that is often explored in Western cinema. Much like the juxtaposition of the Jedi and the Sith, the western genre has always featured characters who represent pure good, often depicted as lawmen or Christian, and pure evil, often as outlaws – or sadly Native Americans and racial minorities. And then there are cowboys, who usually fit into the indefinable area in the middle as ‘anti-heroes’. Most prominent in the first 2 seasons, Din could easily be defined as ‘morally grey’, a trait rarely seen in Star Wars films which often focuses on the battle of moral absolutes that the Jedi and Sith are forever engaged in. While Din does commit good deeds throughout the show, he often does so for selfish purposes. In Season 2 he aids Cobb Vanth (played by Deadwood star Timothy Olyphant), a local lawman, in defeating a Dune-like Krayt Dragon that threatens a local town. While Din does help Vanth achieve something ‘morally good’, he only does so to reclaim a set of Mandalorian armour.

That particular episode also features a modern take on a slightly problematic Western trope, the relationship between white settlers and the Native population. The episode uses the town’s inhabitants and Tusken Raiders as metaphorical conduits for this troubled history. The episode shows the two cultures overcoming their differences and banding together to fight the Krayt Dragon. While some classic Westerns attempted to view this issue through a contemporary lens, most famously Dances With Wolves (1990), even they tend to ‘whitewash’ a lot of events, leaning on the ‘white savior’ trope, or they explore these relationships purely through miscegenation.

To Star Wars fans, it is no secret that George Lucas was heavily inspired by Westerns (and Samurai films, their Japanese predecessors) especially those produced in Italy when creating and developing Star Wars. The western genre is the heart of Star Wars, and the franchise’s most iconic characters and settings have almost been torn from the screens of Spaghetti Westerns.

Named the ‘Best Movie Villain of All-Time’ by Empire Magazine, Darth Vader’s black cloak and mask have been a staple of Halloween costumes and fan cosplays for just under 50 years. Vader’s signature look is actually based on the intimidating enforcer in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West (1968), commonly referred to as ‘The Man in Black’. Then there is the original ‘Space Cowboy’ Han Solo, whose iconic vest and blaster are staples of costume design from 60s Western cinema. Han Solo also shared similar ‘grey morals’ to his modern counterpart Din, appearing in A New Hope (1977) as a selfish anti-hero, Solo initially abandoned the Rebel Alliance to pursue selfish gains, then returned to the cause for financial rewards. His brother-like relationship with Luke is also reminiscent of the bond shared between the two titular stars of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

Much like how The Mandalorian utilises the ‘cowboy shot’ when framing Din, the original Star Wars trilogy paid homage to many classic Westerns through its cinematography and composition. One of the most famous shots in A New Hope shows Luke standing before his burning homestead, which is actually framed to resemble a similar shot in The Searchers (1956).

Genre cinema is defined by emotion. Each genre hones in on a singular emotion or ideal and explores and contorts it to influence its audience. Naturally, the stories told within these genres can explore more than one emotion, but each genre can be defined by its targeting of a singular emotion. Horror explores fear, Science Fiction and Fantasy explore our sense of wonder, but Westerns are more versatile than that. Film critic Samira Ahmed describes them as “mythic tales”, whereas cinematographer Asi Owen says they explore individualism and independence. It is a sense of flexibility that makes the Western genre so entertaining because it is more than a genre. That isn’t meant idealistically but is to say that the Western is a representation of a specific time period, which has transformed into its own genre. It is this unique circumstance that allows for such flexibility in storytelling and allows the Western genre to explore a range of emotions and ideals.

Even with its Science Fiction elements stripped away, The Mandalorian is a mythic tale of good vs evil and how Din fits in the grey between. It is also a story of individualism that explores a stubborn loner trying to survive in a post-war galaxy – which closely resembles the post-civil-war setting of a lot of Westerns. In a modern world where everyone feels like a slave to their jobs, their phones, and the pressures of modern society, a loner who can do what he wants is an idealistic fantasy that makes Westerns feel increasingly enjoyable and cathartic.

Westerns often mix well with speculative fiction like Sci-Fi because, to modern audiences, a lot of elements of the Wild West seem like speculative fiction. Despite it being just over a century in the past, to a lot of viewers, Westerns feel like a distant fantasy. This only adds to its description as being ‘mythic’. People love myths because, despite their fantastical elements, people once believed they were true. That is why they have such a hold on audiences, it is their ‘fantastical believability’ that immerses audiences and upholds the suspension of disbelief.

As well as their flexible exploration of emotions and ideals, Westerns are also incredibly popular because they were one of the first genres to offer critique and commentary about the reality of a ‘perfect society’. Hollywood cinema before the Vietnam War was often filled with an overwhelming sense of pride for American society, depicting Americans as pure, good-hearted heroes, especially at the height of the Cold War. However, as criticism grew for the war in Vietnam, the art of the time began to reflect this, holding a mirror to a society disillusioned by its goodness. During and after the Vietnam war, the Western genre began featuring American characters that were consumed by hateful morals, or who were regret-filled outlaws looking for redemption. While audiences of the time welcomed these changes, modern audiences have found new relevance in this theme, in an age of political strife, modern audiences feel schadenfreude in the discomfort of previously lorded individuals.

Leave a comment